Tribute to Tradition

Paving the Way… Eddie Lang

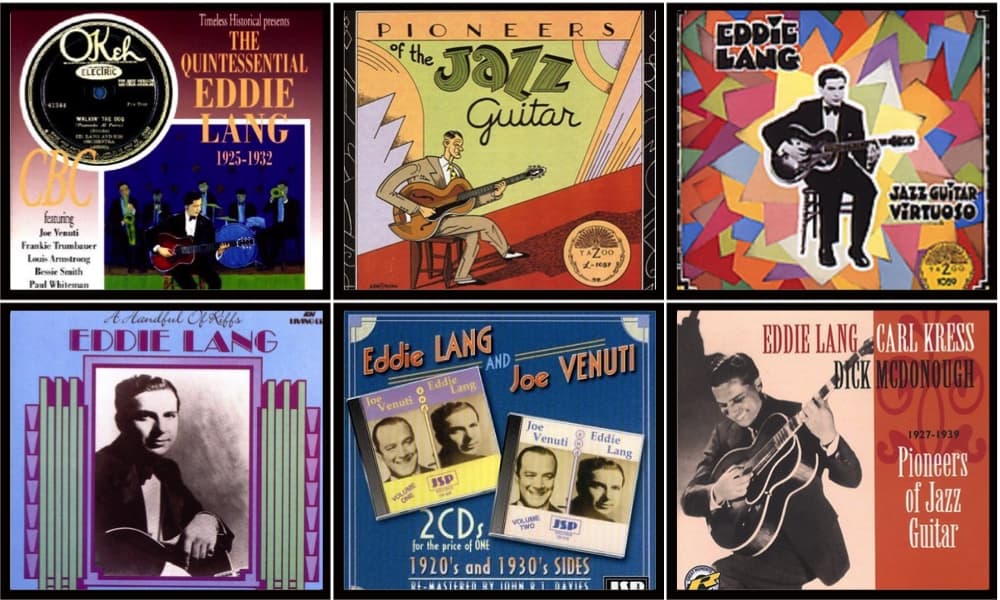

Jazz Guitar Today Pays Tribute to Eddie Lang

Part of our agenda at Jazz Guitar Today is to pay tribute to tradition. Of course, many of today’s players were influenced by the great guitarists of the past. Much has already been written about these guitar legends. Regardless, we thought we would provide some new and unique perspectives. So we reached out to JGT contributor Frank Hamilton to share this thoughts on a jazz guitarist that helped pave the way for many others – Eddie Lang.

Why Eddie Lang?

American folk/jazz musician historian Frank Hamilton explains, “Eddie Lang played with great sensitivity on an acoustic guitar, which enabled the listener to hear subtleties that are often lost on the electric due to the frequencies lost in amplification. He was extremely versatile, and comfortable with different styles of music.”

“Eddie got a lot of tonal mileage out of the acoustic guitar and like Freddie Green, his rhythmic approach drove the square sounding Whiteman band. Eddie also knew when to play fancy single string solos and when to lay back to support others in the band. It was an education to hear him play.”

Frank continues, “Eddie Lang was versed in sophisticated harmonies for his time which was to influence many later jazz guitarists in their ability to reharmonize and re-work existing basic chords. I began to appreciate the timbre and the dynamic range of the jazz acoustic guitar, how when close mic’ed it could be gentle one moment and driving the next. A lot was lost when Charlie Christian opened up the amplitude of the guitar although the horn-like solos were gained. Joe Pass recorded an album with just his unamplified guitar which is the sound he preferred.”

To say Eddie Lang was the major influence in the rise of the jazz guitar is an understatement.

His playing almost eclipsed the 1920’s tenor banjo as the primary stringed dance band rhythm instrument. The banjo in the early days of recording was able to cut through brass instruments in a New Orleans Dixieland band but into the cylinder discs invented by Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell’s follow up of the Graphophone.

In 1887, Emil Berliner invented the flat disc record. His device was called the Gramophone and developed an early microphone as well. Eventually, the condenser microphone would enable even more close mic use. Who better to exploit the new rhythm sound on the guitar then Eddie Lang.

Eddie was born Salvatore Massaro, the youngest of nine, to an Italian-American instrument maker, Dominic and his mother Carmela in South Philadelphia on October 25, 1902.

He later changed his name to that of a local basketball player. South Philly in those days was a rough neighborhood, a headquarters for the Mafia and was known for street gangs. One of Eddie’s oldest friends from that time was Guiseppe “Joe” Venuti, born a year younger than Eddie. Although they were friends, their personalities were decidedly different. Eddie was amiable and got along well with all of his musical associates in contrast to Joe whose passions were violin and fist-fighting. Joe was known to break inexpensive fiddles over some poor musician’s heads. You can take a boy from South Philly……..

Eddie and Joe both studied the violin. From the same neighborhood, they studied at James Campbell School together.

Professor Ciancarullo gave Eddie, at the age of 13, a grounding in classical music, theory and harmony. Eddie and Joe jammed as kids together and Eddie began to experiment with the guitar. They played mazurkas and polkas impressing each other with their respective chops. They could both switch off, Eddie on violin and Joe on guitar.

Django, who played Musettes prior to his jazz recordings said that Eddie showed him the way to his career with Grapelli. Coincidentally, Django also started his career on the six-string banjo, prior to his hands being burnt in a Gypsy caravan fire and his switch to guitar. There has been a rivalry among guitarists as to whom was the better player. This question even reached the dialogue of an Ernest Hemmingway novel.

The banjo was the popular band rhythm instrument of the day and a sixteen-year old Eddie played it in 1918 at his first job where doubled on guitar.

Eddie grew up near South Street noted for blues musicians in a largely black area of Philly. An influence was Bobby Leecan, an obscure bluesman. Eddie was later to record with Lonnie Johnson, the famous blues guitarist changing his name again for this recording to “Blind Willie Dunn” as a tribute to Blind Lemon Jefferson and because it was marketed in the segregated race records. Two volumes of this duo have been reissued.

In his neighborhood, Eddie, a well-rounded versatile player was exposed to a variety of folk music, Italian, Jewish, African-American and others making him a sought after accompanist for studio work, perhaps the most prolific studio musician of his time.

His sojourn with the banjo was short-lived. Lloyd Loar developed the Gibson L4, an arch top with a round hole. It could cut through a band as effectively as a tenor banjo and it would be replaced by the L5 which had f holes and became state-of-the-art for the dance and jazz bands of the 20’s and 30’s largely due to Eddie’s innovations. The guitar along with recording advances made the banjo a second-class citizen.

Bands became costly to hire for gigs so at 22 years of age, Eddie joined a small combo called “The Mound City Blues Blowers” featuring Red McKenzie on tissue paper and comb and with Dick Slevin on kazoo, Jack Bland on banjo and Eddie on guitar.

They were a novelty act that sold records and were cost effective for dinner parties, weddings and other smaller gigs. Tiger Rag and Deep Second Street Blues were two of the earliest recordings Eddie did with the Blues Blowers who were popular in England as well as the States.

Eddie once again teamed up with his childhood partner Joe and made memorable recordings in 1926 for Okeh Records. One remarkable tour de force was their song, “Wild Cat” which displays Eddie’s virtuosity as an excellent accompanist. At the age of 25, with the legendary Bix Beiderbecke, the famous cornet player, Eddie’s musical addition to “I’m Coming Virginia” made it a jazz classic.

At the age of 27, Eddie joined the Paul Whiteman orchestra, string heavy and stodgy requiring jazz musicians to spice it up who could improvise, not just read the charts.

Bix Beiderbecke, Joe Venuti and Eddie provided the spark. Whiteman made a film in 1929 called “King of Jazz”, a complete misnomer since he was anything but.

Eddie, Joe and Bix saved the day. It was through Harry Barris and the Rhythm Boys performing with Whiteman that Eddie was introduced to Barris’s lead singer, Bing Crosby. The two became instant collaborators and friends. Eddie developed a rich single string technique as Bing’s guitarist. You can hear it on Bing’s theme song for his radio broadcast, “When the Blue of the Night Meets the Gold of the Day”. As Bing developed his close mic crooning style from that of a skilled hot jazz singer, Eddie also refined his technique to accommodate the softer new trends in music that paralleled the advances of the recording industry.

Eddie’s untimely death at the age of thirty due to a failed tonsillectomy was a blow to the guitar playing world.

I’ve always maintained that there are two things that make a musician successful, 1. Playing the right notes at the right time and 2. Making others sound good. Eddie was a master at both.

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons2 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Analyzing “Without A Song”

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons4 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Considering “Falling Grace”

-

Artist Features1 week ago

New Kurt Rosenwinkel JGT Video Podcast – July 2024

-

Artist Features2 weeks ago

JGT Talks To Seattle’s Michael Eskenazi