Features

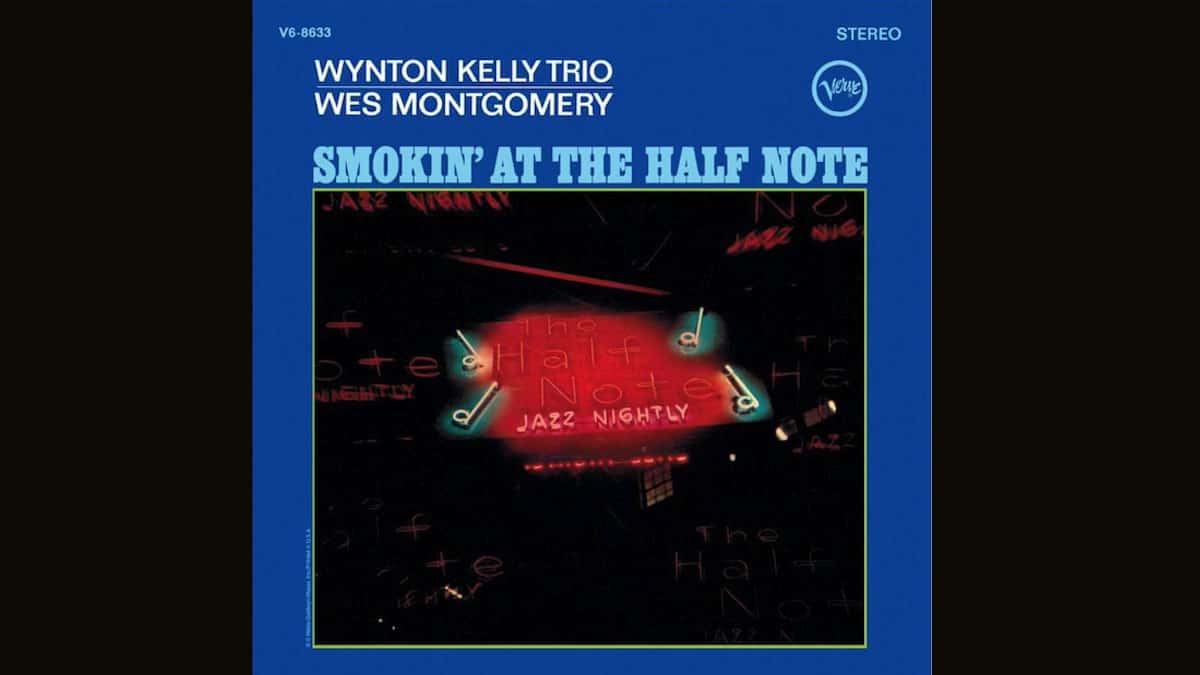

Paying Tribute to Wes Montgomery’s ‘Smokin’ at the Half Note

JGT contributor Bob Tarkington offers up a deep dive into Wes Montgomery’s classic album, ‘Smokin’ at the Half Note

John Leslie “Wes” Montgomery was born March 6, 1923 in Indianapolis, Indiana. He and his brothers moved with his father to Ohio where, at age 12, his brother bought him a tenor guitar. It wouldn’t be until age 19 when they moved back to Indianapolis that he would buy a six-string guitar and teach himself to play it. His motivation for learning to play came from hearing Charlie Christian play and he set out to learn everything that Christian recorded. He could not read music and had no training in theory, but he had a keen ear for the music and developed his own unique style playing with his thumb instead of a pick.

Lionel Hampton was impressed by Montgomery’s playing after hearing him in a club in Indianapolis and brought him on tour with his band in the late ’40s. While it may have been a good learning experience for Montgomery, it did not fit with his professional ambitions or his family life. He was also afraid to fly and had to drive himself from city to city to keep up with the band. After a little more than a year, he returned to Indianapolis. There he worked at a factory job during the day and played in clubs with various groups at night. He often played and recorded with his brothers, Monk and Buddy. They got a recording contract with Pacific Records under the name “Mastersounds” and Montgomery went out West to record with them. After a short stay, he returned to Indianapolis to resume his factory job and focus on club dates with his trio including Melvin Rhyne on the Hammond B3 organ. Embed from Getty Images

This time, it was Cannonball Adderley who heard Montgomery play in a club in Indianapolis and was so impressed by his playing that he convinced Orrin Keepnews to record him at Riverside. His first recording with Riverside, The Wes Montgomery Trio included Melvin Rhyne on organ and Paul Parker on drums and included his now well-known version of “‘Round Midnight.” During this time, Montgomery got opportunities to play with John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, and recorded with Miles Davis. From 1959-1968 he was leader on 21 albums and appeared as s sideman on several others. Full House, recorded live at Tsabo in California included the solo, “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” where his thumb technique created a uniquely beautiful sound. Montgomery’s career came to a sudden end in June of 1968 when he died of a heart attack at age 43.

Smokin’ at the Half Note was recorded by Wes Montgomery with the Wynton Kelly Trio under the Verve label. Riverside had filed for bankruptcy when one of its founders died suddenly of a heart attack and Orrin Keepnews moved with him to the new label. While his 1960 recording on Riverside, The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery is often cited as his finest recording, Smokin’ at the Half Note is unique for featuring the trio that accompanied Mile Davis in 1959-63, the live setting, and most importantly, for the extended pieces that demonstrated the range of Montgomery’s ideas as an improviser. Two of the numbers on the original release (“No Blues,” “If You Could See Me Now”) were recorded in

By the time of this album, Wes is firmly established as the preeminent jazz guitarist. He has fully developed his classic pattern for solos with single note improvisation followed by choruses using octaves and closing with drop 2 chords that emulate the horn section of a big band. His dexterity with his thumb is remarkable. Most of his notes are struck with a downward motion of the thumb. Faster passages are made possible with slides, hammer ons and pull offs with his left hand or sweep “picking” with his thumb across adjacent strings. An occasional up-stroke using the nail of his thumb is observable based on the videos available of his playing.

The first cut on the album is “No Blues.” This is an extended 12-bar blues piece in F with stretched out solos by Wes and Kelly. Wes’s solo runs for a full 292 bars or 24 choruses lasting almost six minutes. He begins with simple phrases and rock-solid swing feel with 8th notes. He picks up the feel of tempo with 16ths and longer runs on the fourth chorus. The fifth chorus is a series of quarter note minor 6th interval of G to Bb against the entire progression highlighting, depending on the chord, the 9 and 11, the b3 and root, the 11 and b13, the root and b3, and the 5 and b7. Wes begins to insert the occasional octave in chorus six and by chorus 8 is fully engaged in octave playing. Chorus 12 combines octaves with chords for an accelerating effect. In chorus 14, Wes plays the head in chords and gives the impression that he may be ready to turn the solo over to the next player. But then he charges ahead with further chordal embellishments on the melody. Chorus 17 introduces an exciting chromatic sequence of chords using a common 3 note fingering for a 13 chord running in 8th notes for the first four bars. This run starts on an F# over the F7 chord bringing and altered sound. Wes was not a theorist and made his mark by playing what sounded good to his ear. He returns to the idea of one harmonic device, an A, Eb, and F# for the entirety of chorus 20. Finally, the solo closes out with four choruses of octaves with chords interspersed. It is a breath-taking example of the wide range of rhythmic and harmonic capability of this musician and must have been thrilling to the live audience they played for. Winton Kelly is fully up to the challenge with his solo. Paul Chambers adds a few choruses on the bass and Wes closes out the tune with the head.

“If You Could See Me Now” opens with an ornate introduction and melody played by Winton Kelly. A piano solo follows embellished with an occasional note and later, subtle comping chords from Wes’s guitar. Wes’s solo is taste-full outlining chords with a variety of rhythmic figures. He uses a C pedal in measures 13 and 14 which sounds the sharp 11 for Gb7, the 5th for F7, the 9 for Bb7, and the 13 for Eb7 punctuated with approach and grace notes. There is a bluesy feeling elicited from playing the b3 over the Abmaj7. A characteristic “Wes phrase” is added with a descending 16th-8th note line in measure 19. He closes his solo with an impressive chorus of octaves. Kelly closes out the number with an embellished head.

“Unit 7” opens with a statement of the melody by Wes followed by a Winton Kelly solo backed by Wes’s comping in very light guide tones to stay behind Kelly’s solo. This is a technique worth remembering. Wes follows with a 3 ½ minute solo featuring single lines, octaves and chords. The form of the song is a 12 bar blues section A and an 8 bar bridge of ii-V and iii-VI repeated. The last line of the A section varies each time with use of a bVI

Wes demonstrates his ability to create melodies and utilize short motifs in his composition “Four on Six”. This tune is built on the Summertime progression with added ii-Vs in the second four bars, a composition technique Wes used in other compositions like his ¾ time West Coast Blues. The added ii-Vs gave Wes more material to build interest in his solo lines. Here he opens the solo with four bars of call and response focusing on the 9 and 11 of Gm answered by 5-7-1. He then simplifies this motif to the 9 and 7 of each chord following the progression of ii-Vs. Another repeating motif occurs in the next ii-V progression where he plays the root, 9, root, and 13 of each dominant chord with rhythmic variations and a final variation to complete the “question.” Wes omits his characteristic chordal section of the solo, but add it during a section of trading fours at the conclusion of the piece.

“What’s New” is a ballad opening with Wes playing the head with octaves. Wes’s solo follows a tasteful few choruses of improvisation where he returns to the melody with octaves. This is more of a showcase piece for Winton Kelly than Wes.

What is clear from this simple analysis of this recording is that there is much more depth to be realized from the study of Wes Montgomery’s playing on these songs. “No Blues” alone would represent a significant piece of learning when analyzed in detail and played with the swing and timing of Wes. Wes Montgomery left a huge legacy of melodies, motifs, rhythms, and harmonies for every guitarist to follow.

Article by Bob Tarkington for Jazz Guitar Today

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons2 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Analyzing “Without A Song”

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons4 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Considering “Falling Grace”

-

Artist Features1 week ago

New Kurt Rosenwinkel JGT Video Podcast – July 2024

-

Artist Features3 weeks ago

JGT Talks To Seattle’s Michael Eskenazi