Artist Features

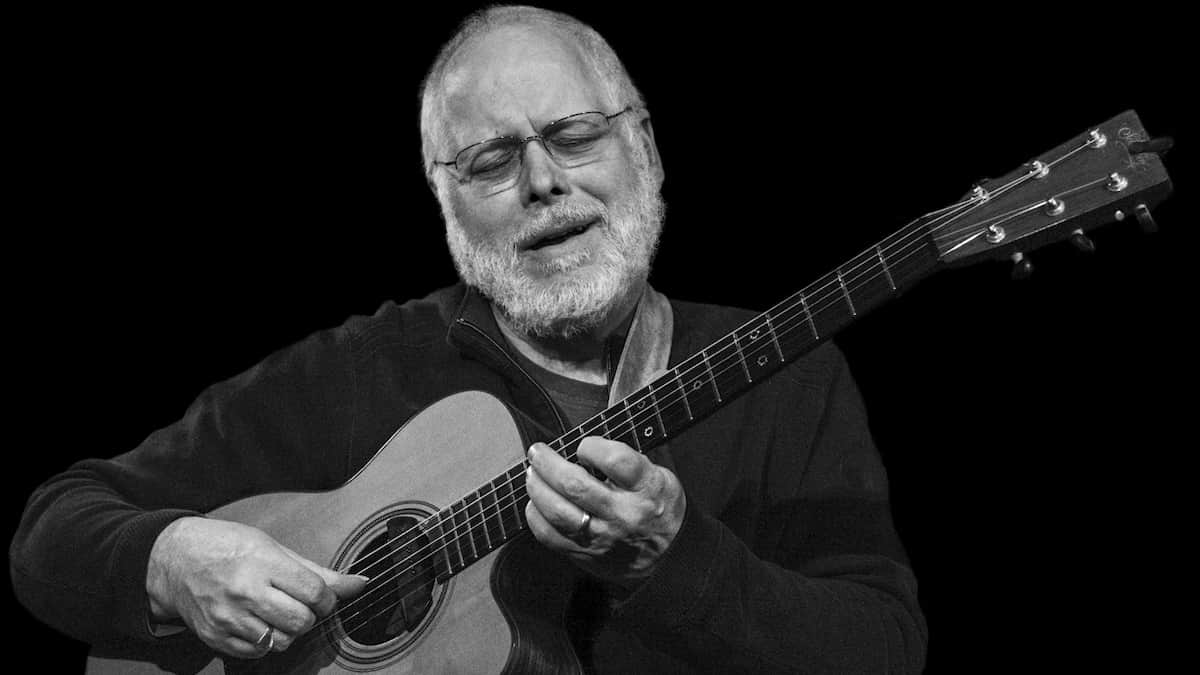

Interview With One Of Seattle’s Finest, Jamie Findlay

Jazz Guitar Today contributor Joe Barth interviews guitarist Jamie Findlay – discusses his development as a guitarist and the albums that influenced him.

Active in the Seattle jazz scene is guitarist Jamie Findlay. Jamie was born in Seattle but most of his performance and teaching career was in Los Angeles. Moving back to the Seattle area, Jamie performs in several settings, most often leading his own group or in a combo with saxophonist Brent Jensen or a guitar duet with Tim Lerch.

Above photo credit: Cathy LaFever

JB: Were you living in the Seattle area when you started to play jazz guitar and what inspired you to take up the guitar?

JF: I grew up in the Seattle area, born & raised. My father had some excellent piano skills, his specialty being boogie-woogie. Music in the house ran from Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Hank Williams, Los Indios Tabajaras, Ray Charles, Big Band, the Beatles, Creedence, The Doors, Rolling Stones, Seals & Crofts, and everything in between. I was encouraged to start studying piano by the age of 5. I was drawn to the Brothers Four, a local Seattle folk group, and was determined at age 8 to be the 5th brother. However, I couldn’t do that without being a guitarist, so I began pleading for a guitar, and my parents heard me and gave me a guitar for my 9th birthday.

JB: What was most helpful in your personal development as a guitarist?

JF: I can think of at least four things that were the most helpful to me:

First, having supportive and loving parents that shelled out for music lessons, and drove me to guitar lessons every week, without fail. God Bless them.

Second, at age nineteen getting my first gig, playing six nights a week, for two years straight, at least four hours a night (yes even the silly disco music with constant 16th note strums). I just don’t think those opportunities exist much anymore. Thirdly, having the good fortune to study, and be really enamored of, music theory at a young age. To be able to understand how all the ingredients of music go together, and to have the good fortune to teach it for several years, is really the heart of the issue for me. Fourthly, having the support of my family, my wife, and daughter, has probably been the most important thing. I think there are other important things, like practice, visualization, opportunities to perform, repertoire, etc… but those first four are it for me.

JB: To you, what are three of the most influential jazz guitar albums and why?

JF: Wes Montgomery, the Bumpin’ album.

I love the solo on “Here’s That Rainy Day.” He starts with the melody in octaves, and he has a great Bossa feel going on when the more common setting is a ballad. His solo starts with single notes, then goes into octaves. His note choice and his motivic development are awesome. I’ve heard people poo-poo the orchestra thing on some of the Wes stuff, or the fact that he covered some pop tunes, but the truth is that those arrangements brought more attention to his artistry, and they are so classic. Also, check out some of the musicians on that recording; Grady Tate on drums, and Roger Kellaway on piano. His time and feel are exemplary. Now the guy didn’t start playing till he was 20, and he completely shifted the landscape of the guitar. This is from a guy who didn’t read or write music. Whenever I hear him, I smile. His sound is so warm and full of love. I’ve heard stories that he was a great friend and a wonderful family man. I can’t claim to have heard all of Wes’ stuff, but I’ve never heard a mistake or a poorly played line, a bad note, a poorly composed song, or a boring solo. His tunes are wonderful. There are also a few solo pieces he recorded out there, amazing! When you remember how poorly the African/American community was treated in the 50s and ’60s, and here’s a gentleman of color playing guitar, changing the landscape of the instrument, exuding love and happiness that reaches 5 or 6 decades, or more, beyond he’s efforts, that’s an accomplishment. I want to be just like him when I grow up.

#2, Joe Pass, Virtuoso.

When you listen to this recording, the sound says “BUDGET RECORDING SESSION.” But what he’s playing is amazing. And all on his own. His time, note choice, and execution are flawless. And his groove is so swinging. I love his selection of tunes too. I used to try to play along with him. Not very often did it sound good, but a couple of times I liked what I heard. I got to see him when I was younger, and he used to come to GIT/Musician’s Institute when I was teaching there. One time I was sitting in the teacher’s lounge by myself, practicing, and unbeknownst to me, Joe came in (I heard the door open, but I was practicing and trying to keep my mind on what I was working on). He came up and looked over my shoulder at my right hand (I play fingerstyle) and he was checking out my technique. After about 30 seconds, he made a comment, which startled me. I didn’t realize he was directly behind me, looking over my shoulder. He asked how I developed my technique, I guess he liked it. That was pretty cool. He was a very nice guy. Another time he was doing a workshop at GIT when I was a student in 1978, and he invited anyone to come up and play. I was fearless back then. I figured what didn’t kill me would make me stronger. So, I went up and tried to play “Here’s That Rainy Day” with him. I hadn’t memorized the tune yet, so he commented on the changes I played. That stung a bit, but I made sure I had the changes in my head moving forward, on any tune.

#3, Ralph Towner Ana.

This record is so well recorded. The sound of Ralph’s classical guitar, and his 12-string, are just mesmerizing, and his compositions are stellar. The timing and his ebb and flow on the “Reluctant Bride” are so thoughtful, as is the solo. “Joyful Departure” is indeed Joyful. The solo section on this has a lively step. “Green and Golden” is so beautiful and almost regal. “Veldt” is nothing more than a riff, but leave it to Ralph to make a full-fledged event out of it. The “Seven Pieces for Twelve Strings” are sweet little vignettes, not much more than 3 minutes each and most much shorter, but he always finds such nice moments of little happenings on the guitar. Ralph does a thing with his 12 string, where he’ll tune his bigger strings to a particular chord, say Cmi7, then he’ll tune the octave strings adjacent to the bigger strings, to the extensions of the Cmi7 chord, and what he likes to do then, is improvise. Gosh, he’s great at it too. I believe the last piece on the recording is an example of that “Sage Brush Rider.” What a terrific recording. There was a time when I listened to Ralph almost exclusively. His playing and compositions were a big influence on me. His compositions have their roots in classical music, with a firm hand in contemporary music and jazz. I really love all the stuff he did with Oregon, and I love the way that band morphed after the untimely departure of bandmate Collin Walcott. I met Ralph a few times; once we both were at a guitar festival in Osnabrück, Germany in 1998. We planned to get together in Seattle later in the year when we would both be there. At that meeting, he met me in the street at the mailbox, where he had just received the recording of music from a live concert performed in Finland with a Symphony. He took the DAT tape out and we immediately started listening to it. We listened to one of the pieces, which, he said, was a compositional idea he had, where he wrote thirty little snippets of music, thirty little riffs that went together, but they were arranged in three columns of ten motifs, and the orchestra was divided into three parts, each with ten of the thirty motifs. It was the conductor’s job to tell each section of the orchestra which motif to play while the members of Oregon improvised over the soundscape the conductor and the orchestra were creating. I could feel my mind explode, when Ralph said, “Want to see the score?” “Heck yeah,” was my response, and as the DAT tape continued to play the piece, Ralph ran upstairs, returning within about thirty seconds with a self-addressed package which he ripped open, and unfolded the conductor score of the thirty snippets of music. Ralph asked, “Where do you suppose we are?” I was able to recognize one of the motifs the orchestra was playing. I had never considered the possibility of an entire orchestra complicit in a grand scheme of improvisation. My mind was blown. The piece was later recorded with the Moscow Symphony and is called “Free Form Piece for Orchestra and Improvisors.” Ralph Towner, pushing the envelope. At another time, probably in the early 2000s, Oregon was doing a tour and was performing in Los Angeles. I was able to meet with Ralph and we had a nice sushi dinner, and I hung out with him a little before the show, and we traded the guitar back and forth, showing each other riffs, and playing tunes for each other. I had just finished composing a solo piece entitled “Unity;” which has some rather radical changes that shouldn’t go together, but I think they sound good. So, I decided to play that piece for Ralph, throwing caution to the wind. When I finished the piece, there was a short quiet pause, and then Ralph said, “Man, play that again!” It was one of the nicest things anyone has ever said to me. We could go on and on here, listing great guitarists; Pat Metheny, Jim Hall, John Scofield, Terry Kath, Hendrix, Stevie Ray, B.B. King, Jeff Beck, Joe Diorio, Jimmy Wyble, Ron Eschete, Don Mock, Howard Roberts, Lenny Breau, Ted Greene, John Pisano, Bill Frisell, and many more, and how they all have either held up, or bolstered the guitar in such a unique way, or completely blazed a new trail, and in many ways pointed out completely new directions for us all to go blazing our own trails.

JB: How did living, playing, and teaching in Los Angeles change you as a player?

JF: Well, I got to live in LA from the mid-’70s to 1980, then again from 1985 through 2015. When I was younger, I just wanted to be able to play, create music, and write songs, along with some good artists. There was always so much opportunity in Los Angeles. It’s such a large area. One of the amazing things that happened to me over and over again would be I’m on some gig, a random call from someone to whom I’ve been recommended for the gig, and I’d meet the people on the bandstand, and on the break, I’d ask them about themselves and how long they’d been in town, and they’d answer fifteen years, or twenty years.

Usually a long time, and I’d have fifteen or twenty years, doing the same thing, going out to calls, and I’d keep meeting these great players that had been there as long as I had been there, and I had never heard of them. It’s really a huge area, and people come from all over to play and try to have music be their livelihood. It was very rich with musical resources.

As I said earlier, I always assumed that I would mostly play and create music, but I was given the opportunity to teach guitar, and I found I enjoy it. I love helping people understand the inner workings of music and guitar, and I get a lot of satisfaction out of it. When I see my students doing well, it makes my eyes water. Because the LA area had such a draw for musical people, it’s a no-brainer that music education would become such a viable commodity in the area. Shortly after GIT started, in the late 70s, a lot of the universities and colleges in the area started to develop programs and curricula to draw more students to the area to study music. The Dick Grove School, the USC Studio/Jazz Guitar Program, the UC system, and the California State system all started to develop their music schools along the lines of what GIT did, but more of a four-year, Bachelor’s system. That’s when MI (what GIT morphed into) started offering a four-year program. The great thing about teaching for me is that the more I teach, the better I play. I like to think that I’m teaching the students, but in reality, the students are teaching me. I truly owe them a huge debt of gratitude.

JB: Reflect upon recording your duo record with guitarist Duck Baker.

JF: Duck and I met in Edenkoben Germany in 1994. We both had made some records released by the great acoustic guitarist Peter Finger, and his Acoustik Music Records at the same time. Peter would bring guitarists to Germany and we’d all pile into a van and hit the road for a couple of weeks, or he’d do the Guitarren Festival in Osnabrück. Always a great adventure, and great audiences in Germany. They love all kinds of music and really enjoy listening to and being with you. So, around 1998, Duck invited me to come to the Bay Area to perform and start working on a record. We would book these little tours, the Bay Area, southern California, Idaho, and maybe Nevada, but usually we drove straight through Nevada, Washington, and Oregon, he also had this great connection in Nashville to play and teach at the Chet Atkins Appreciation Society (CAAS) so we did that several times (always great for some southern food experiences). We would play some tunes together, then one or the other of us would play a solo. This went on for several years, and then we took some time to record an album, called ‘Out of the Past’ on his label, Day Job Records, which came out in 2001. Duck had a friend, named Jim Nunnally, who lived in Crocket California, close to where Duck lived, who had a little studio. He also had an 1863 Martin in just immaculate condition. That’s where we recorded. Duck likes to find these unusual tunes, and then we’d work on making them even a little stranger. He always had a great place for us to play in the area, and we had a lot of nice adventures. We had been out of touch for a few years, then he sent an email, and it was just like old times. He had been going through some of our live concert recordings and some of the recordings we never put out, and we’re trying to gather enough stuff to release some new material. There are some live recordings that sound great. I’m pretty amazed that we played so tightly together. Look for that new release this year.

JB: You made two Paul Desmond tribute CDs with saxophonist Brent Jensen. Reflect upon Jim Hall’s and Ed Bickert’s influence on you in these projects.

JF: Brent is really an amazing musician, a super smart guy, and a great teacher. I’ve seen the results of his students, both on sax and on other instruments. Paul Desmond and Dave Brubeck had a pact; Paul wanted to play outside the Desmond/Brubeck, so Dave asked if Paul would not play with other pianists, so Paul chose guitarists. So, the most chosen of the herd were Jim Hall and Ed Bickert. If you listen to the early Paul Desmond – Jim Hall stuff, to me it is amazing to think that there is such deep, modern-sounding, musical stuff happening in ’59, and the early 60’s. I guess it shouldn’t surprise me, I remember my 4th-grade music teacher at elementary school playing “Take Five” for our band class. That had to be the early or mid 60’s. Now I didn’t listen to Jim Hall or Ed Bickert as I listened to Wes, Joe Pass, Pat Metheny, or others, but after Jim Hall passed away, I did start listening to him. I think it’s rare to hear a guitarist like Jim Hall, who plays sort of minimalist, not a lot of notes; but what he says with those notes seems to say a lot more than most guitarists. And the way he comps or supports Paul Desmond is untouchable. And as far as Ed Bickert goes, I can’t think of anyone who makes a Tele sound like a big-bodied jazz guitar. And the stuff he plays is beautiful. Behind Desmond, he’s so supportive. He waits and plays in Desmond’s gaps, never in the way, always in the background. And when Bickert solos, he almost takes the same stance, melodically; playing in a similar flow and rhythm as Desmond, never outshining, and always using some really great guitar ‘tricks.’ When I’m playing with Brent, I just try to not sound stupid. So far it seems to be working. I can only strive to point my playing in the direction of Jim Hall and Ed Bickert. I don’t expect to reach their accomplishments. I also want to point out that Brent and I have a new duet recording, ‘Jamie Findlay and Brent Jensen.’ It’s on Spotify, Apple Music, and most of the streaming outlets. I am happy with it. Brent sounds amazing, and I feel we are really hitting our stride together. Also, I love the sound of my guitar on this recording.

JB: Over your stellar career as a teacher, what are some traps that guitar players get themselves into?

JF: That’s a great question, Joe. There’s no shortage of traps or problems we can get ourselves into. I guess the most common thing I see with guitar students is that we think in shapes, rather than in musical ideas. The shapes aren’t so much the problem, but linking the shapes to how the music actually works is the issue. I always write my lessons out in standard notation and then add chord diagrams. I often add classical guitar nomenclature, and tablature, so that any level of guitar student can grasp the concept. I don’t see enough guitar students burying their heads in music, not tablature, not chord diagrams, but music – you know like how all other musicians read, write, speak, and listen to music. My reading teachers used to say we should have thirty pounds of music books to read. I recommend the Bach violin partitas and sonatas, and the cello suites for guitar, the Bach inventions, a guitarist can learn both parts and record themselves playing both parts. There’s a great book published by Hal Leonard, the ‘Real Little Classical Fake Book,’ or the H. Klosé clarinet method. This is all stuff that can help with musicianship and reading. I’m serious about this, almost evangelic, but I speak from experience. By all means, learn as many shapes as you possibly can, but think in a musical way, and once the shape is written out, write it on the staff, so other musicians can absorb it. Tear apart the music of Bach, Ravel, Wes, Metheny, the Beatles, or whomever. But think about it in a musical way. And then put it in all keys. I always think it’s good to find a mentor or a teacher that can show you different ways to think about the music. And transcribing is useful. Even so far as writing things down on the staff. That’s where the music lives. And that’ll help keep you in touch with how the music works. Also, I don’t see enough students playing their scales in all keys and their arpeggios in all keys. I’ll stop there. I don’t want to be negative, music is supposed to be a positive experience.

JB: You now live in La Conner, a little town north of Seattle. What do you find rewarding in your career now?

JF: I love it here. It’s quite small, but very quiet, and has really beautiful surroundings. It’s close to Seattle and Vancouver, BC, in case we need to get into the city. The first few years were quite slow, but I found a few good folks to play music with, now I play in about 5 or more ensembles and a big band. I get to play with saxophonist Brent Jensen, in duo, trio, and quartet settings, occasionally a quintet, (we even got to play with a community symphony – that was a first!). I’m also doing a jazz guitar duet with the wonderful Tim Lerch, I teach at the local college. I have some private students and do a little theatre work. It’s keeping me pretty busy, and have no complaints. I’m constantly writing arrangements for myself and for my students, practicing my Bach, and my standards, and trying to get my own compositions under my fingers. I’m a very lucky soul, as I get to play music for my livelihood and for my own personal enjoyment and help people get better at their music as well. Somebody pinch me.

Subscribe to Jazz Guitar Today – it’s FREE!

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons2 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Analyzing “Without A Song”

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons4 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Considering “Falling Grace”

-

Artist Features1 week ago

New Kurt Rosenwinkel JGT Video Podcast – July 2024

-

Artist Features3 weeks ago

JGT Talks To Seattle’s Michael Eskenazi