Features

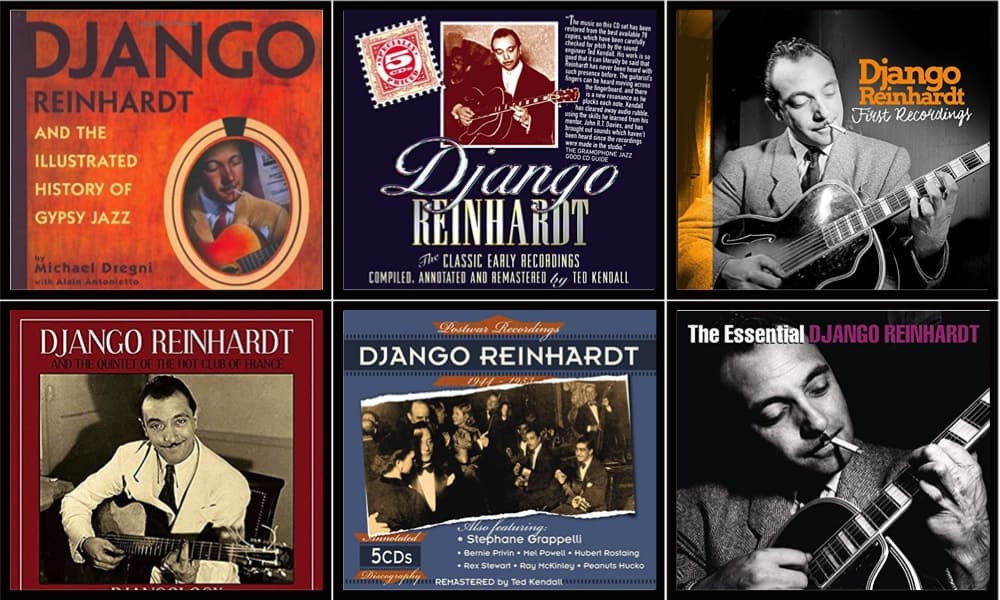

The One and Only Django Reinhardt – Part 1

It would be easy to make an argument that perhaps the most important component of jazz is freedom.

One person might say a swing feel is more important, another might cite the appropriation of a certain form, and still another might reference certain harmonic contexts. But if the player doesn’t improvise freely, reacting spontaneously to what is going on around him or her, while it may be great music, it isn’t necessarily jazz. Certainly the level of ability that every jazz musician aspires to is that freedom to be able to play anything that one hears in that moment, to be a virtual sonic alchemist, capable of reacting instantly and create any mood, effortlessly. For most players, that level of ability is simply unattainable, granted by the musical gods to a precious few. But thankfully, each generation has produced a select group of such virtuosos who then become a beacon of inspiration to those of the same age and to those who follow in the succeeding generations. Art Tatum on the piano, for example; Charlie Parker on the saxophone; and for the guitar, there is Django Reinhardt.

It is no exaggeration to say that Django’s recordings are the very definition of freedom. While Eddie Lang from the 1920s had certainly given the jazz world single note soloing on the guitar, Django effectively revolutionized the role of the guitar, exploiting the potential of the instrument in any style he deemed appropriate in the moment. And doing all this with a left hand damaged in a fire when he was 18 makes his accomplishments all the more noteworthy.

Let’s look at some of his contributions and see how they have influenced the playing of some contemporary gypsy jazz guitarists…

…as well as guitarists in other styles, starting with his unaccompanied playing. While Art Tatum and others had been doing this, the notion of creating a unique improvised piece was a new concept for guitarists.

Among his early recordings is his famous Improvisation #1 from 1937:

Here are two from the mid 1940s, Improvisations #5 from 1947:

Improvisation #6

This sort of spontaneous playing has left its mark on the contemporary players influenced by Django.

Every great player is now expected to be able to extemporize an unaccompanied piece. And one of the wonderful qualities of the Selmer/Maccafarri guitars used in this style is that because of their unique timbre, they can not only sound like an acoustic archtop, but also suggest a flamenco/classical guitar. Here is Bireli Lagrene, perhaps the greatest Django influenced player on the scene today, improvising a Baroque style piece:

Another great player, Adrien Moignard, improvises…

These sorts of unaccompanied pieces can be self-contained and stand alone, or be integrated into an intro for another song. Listen to 14-year-old Antoine Boyer as he improvises a very Django-like intro:

As an accompanist, Django was unparalleled in his ability to drive any ensemble, whether it be a duo or big band.

He was endlessly inventive and unpredictable, alternating between playfulness and seriously smoking swing. Drums or no drums, Django makes the music drive. His early rhythm playing predominately utilized a style known as ‘La Pompe’, which essentially implies a bass drum on beats one and three, and the snare drum on beats two and four. Imitating a train as it starts off and then speeds out of control, Django displays his rhythmic virtuosity in ‘Mystery Pacific:’

View Part 2, where we continue to explore the styles and inspiration of Django Reinhardt.

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons2 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Analyzing “Without A Song”

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons4 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Considering “Falling Grace”

-

Artist Features1 week ago

New Kurt Rosenwinkel JGT Video Podcast – July 2024

-

Artist Features3 weeks ago

JGT Talks To Seattle’s Michael Eskenazi