Artist Features

Growing Up in the Shadow of a Giant

Jazz Guitar Today is proud to feature a rare and exclusive interview – Wayne Goins talks with Grant Green, Jr.

Grant Green, Jr.—the only musical offspring of the legendary jazz guitarist Grant Green—gives us a rare glimpse into the world of the most popular guitarist to ever record for Blue Note Records. Green shares with us what life was like growing up with an icon, provides unique insights on the instruments and techniques his father used, and how his dad influenced his own career—including him getting a chance to work with several of the same artists that played on the Blue Note albums with whom his dad recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio. In a rare and exclusive interview, here is one of the few times Grant Green, Jr. has spoken publicly at length and offered intimate details about the jazz guitar superstar Grant Green.

JGT: Let’s start from the beginning: You were born in 1955 in St. Louis?

GGJ: Yes. I was born in St Louis, Missouri, on August 4th, 1955, in Homer G. Phillips Hospital, which was segregated. It was, at the time, the first and only black hospital in St. Louis.

JGT: What do you remember about your childhood? Was it a musical environment at home?

GGJ: Well, I heard a lot of my father’s music. I know that my grandfather—my dad’s dad—was so proud of my dad and his career. But I also remember that jazz wasn’t the only thing we had around the house when I was growing up. I heard everything from James Brown to the Beatles to Johnny Cash.

JGT: What about your mom—what was she listening to? Did her musical preferences have an influence on you?

GGJ: I remember dancing with my mom as a kid—she was more into the popular music—she always liked Nina Simone, though. Other than that, she didn’t have a direct influence on me, musically speaking.

JGT: Let’s address an issue upfront: You’re officially recognized as Grant Green, Jr., but your actual name is Gregory, correct?

GGJ: Yes, it’s true. When my father realized I was serious about playing guitar and I was about to move to New York in the ’70’s, he and his friend Doc Hymen decided I should use “Grant Green, Jr.” ‘cuz they thought that it ultimately would help my career. Well, that was not necessarily so! [smiles]. I was constantly compared to him. I think it made the bar higher—but that’s another story!

JGT: You’re the oldest of four—there’s Kim, John, and Grant, Jr., correct?

GGJ: Yes—I’m the oldest.

JGT: Did any other members get the music/guitar bug?

GGJ: My younger brother John played the drums for a little while, but I’m the only one that stuck to it. My first instrument wasn’t guitar, actually—it was harmonica. I remember bugging my granddad to buy one for me. He finally did, and I learned how to play by ear really quickly—I could play what I heard note-for-note. My parents and grandparents all noticed it and thought, “We need get this boy a guitar!” So, they bought me a guitar. But you know what? I actually lost interest in it! I was about six years old at the time.

JGT: That was right around the time your dad’s career was really taking off in New York—1961 or so, right?

GGJ: Yes, that’s correct—I remember he wasn’t around much at the time. We were in St. Louis and he was always away from home, mainly in NYC, recording all those great Blue Note albums as a sideman and a leader.

JGT: I’m doing some in-depth research on him, and I discovered that he recorded 17 albums in that year!

GGJ: Wow—I don’t think I even knew that!

JGT: What memories do you have of being with him when he was available?

GGJ: I remember as a kid—maybe 7 or 8 years old, and this one particular time, he took me with him to Kansas City. They didn’t call them bartenders and waitresses back then; they called them barmaids. And I remember, that was the first time I ever had a cherry Coke. The lady poured me a Coke and she poured cherry juice in it! I thought that was the coolest thing ever. [laughs heartily]

JGT: I wonder who Grant was playing with at the time…

GGJ: I can’t recall, honestly. Ya know, when you’re a kid at that age, you’re waay more interested in soda and candy.

JGT: Maybe he brought you with him because he saw you were interested in music and was aspiring to play guitar like him?

GGJ: I gotta tell ya—my dad never wanted me to play guitar—he wanted me to be a doctor or lawyer, or something like that…like most parents do, I guess. Because being in the music industry is a tough life, it’s a tough road. When I wrote that song for my dad called “My Father’s Song,” [released in 2007 on The Godfathers of The Groove album on the 18th & Vine label], that’s when he first realized that I was serious and could actually compose music and play guitar…that’s when he kinda acknowledged it and said, “Okay!”

JGT: With regard to memories of your dad, your former sister-in-law [Sharony Andrews Green] wrote in her 1999 biography, Grant Green: Rediscovering the Forgotten Genius of Jazz Guitar [Miller-Freeman Books], that of all the family members, you’re the one who has the best memory of your dad.

GGJ: Well, I have a pretty good memory now, but not like I used to—haha! I guess she said that because I had more personal testimony regarding the amount of time I spent alone with him than any of the other siblings.

JGT: You moved to Detroit when you were fifteen—had you by then decided to be a serious guitarist?

GGJ: Yes, I was 15 years old when picked up the guitar seriously and never put it down. I was hooked like so many others! I was the only one of the four of us who was living with him when I moved from St. Louis to Detroit when I was a teenager—the other three moved to Jamaica with my mom and their step-dad when she and my dad got divorced. Detroit is pretty much where dad spent the entire second half of his career.

JGT: On page 34 of the book, you told a wonderful story about suddenly channeling your dad’s energy and vibes during a recording session. Which tune are you referring to that that happened?

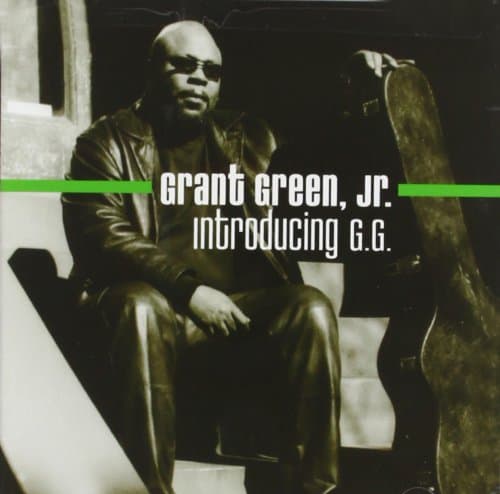

GGJ: That was very strange. It was a song that I wrote “Another Time, Another Place,” which was on the Introducing G.G. album I was working on [2002, Jazzateria Records]. But that particular take of the recording session—when it happened to me—was not on the CD. You know when you’re trying to solo, and it’s just not quite coming together, not flowing, and things sound generic? I just wasn’t feeling it, man. And it’s not like it was a hard tune to play [hums the melody]. But all of a sudden, I felt this thing—this presence—and started playing…and when I listened to the playback, I was like, “Oh, my god—that’s the approach my dad would have taken!” And after that happened, my whole approach changed…I started to see and hear things differently.

JGT: Really?

GGJ: Yeah. You know, when we learn to play, we learn in stages. I think that was when my ears actually opened—playing stuff that I could actually listen to and actually know what it was that I was hearing, and where to find it on the guitar.

JGT: Did you ever spend time transcribing your dad’s solos from his legendary albums by ear?

GGJ: Man, lemme tell ya somethin’—I have never transcribed my dad or anybody’s solo—ever.

Gallery of Albums…

JGT: Really?

GGJ: Nope—I always took what I liked out of the songs. But I never tried to play anybody’s solo note-for-note. We all have these people that we listen to and that we idolize, and I guess that’s cool that you wanna sound like them…but the problem is, it’s already been done. You have to get your own voice—that’s what my ol’ man did, that what Wes did, that’s what George did. If you listen to early George, he sounded a lot like my dad. But eventually he got his own voice, and that’s what we hear and know now as George Benson’s sound. And that’s what it’s about.

JGT: Is it my understanding that George Benson is actually your godfather?? Wow…

GGJ: Yeah, I’ve known George since I was a teenager, he used to come by the house In Detroit to visit my dad all the time. And he’s one of my heroes!

JGT: Your dad wrote “Blues in Maude’s Flat” and “Miss Ann’s Tempo” as a nod to your mom, right?

GGJ: Yes—both those tunes were written specially for my Mom—he really loved her, and I think he wanted to do something in her honor—something special.

JGT: Your dad says he learned mainly by listening to Bird [Charlie Parker] and Charlie Christian—any thoughts/similarities to your approach? Who were your influences beyond your dad?

GGJ: Well, there are many…obviously my father was a huge influence along with George Benson, Joni Mitchell, Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and others. I listened to Yes, Zeppelin, all kinds of people when I was growing up. Herbie Hancock, dozens of other musicians—not just guitar players. I steal from a lot of horn players—because they are solo, single-note melodic instruments. And I listened to a lot of Stevie Wonder—his parents were my next-door neighbors, so I knew Stevie. But you know what? The first album that I listened to that really blew me away musically was Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On.

JGT: Yeah, that album did a lot for a lot of people! And it’s not even an album that you listen to for stealing licks or riffs from—it’s just great classic music.

GGJ: Exactly! Nobody was playing chord changes like that! What an incredible album.

JGT: While doing some research on you for this article, I discovered that in your family’s history, Grant Green died in 1979, and his parents both passed in a relatively the same period. What do you recall of that time period?

GGJ: That was some of saddest times in my life…my grandmother died in 1978, and my father in 1979, and then my grandfather in 1980. My father was an only child, so that entire side of the family was gone in three years!

JGT: Was he a direct influence on what you have become, or did you just learn from buying his records?

GGJ: I learned to play by mimicking him. I used to go to the clubs where he played and watch him. When got home, I would try play licks that I heard him play that night. And I guess some are wondering, what I was doing in a night club at that young age? Well, I was also his roadie! Haha!

JGT: Did you feel stress about becoming a musician?

GGJ: No, I didn’t feel any stress about being a musician until later in my career.

JGT: Shed some light on what it’s like to live in such a long shadow cast by your dad.

GGJ: I think it’s always tough to follow the path of a famous family member—so much is expected of you and you are constantly compared to them.

JGT: Discuss what it’s like being a lefty?

GGJ: Being lefty was tough growing up! There were no lefty guitars—you had get a righty with a double cutaway and reverse the strings. But I played upside down and backwards—a right-handed guitar—for two years before reversing the strings. I can still play that way when I want to. Back in my day, most all guitars were right-handed, so you kinda had to. The problem with that, of course, is that your arm keeps bumping into your tone and volume knobs.

JGT: When did you actually get a real left-handed guitar?

GGJ: I found a real one in Canada, around 1980 when I was doing a two-week tour with Charlie Eckstine—a singer/comedian type guy. The guitar was an Ibanez Artist, built like a 335 model. I found it in Toronto.

JGT: Talk about your connection with Idris Muhammad—you found an opportunity to work with him just as your dad did, correct?

GGJ: Yes, I worked and recorded with Idris. I had a lot of respect for him—a great player and human being! I got to play with a lot of people who worked with my dad. I played with [alto saxophonist] Lou Donaldson [who recorded multiple times with Grant Green]. I’ve known “Papa Lou” for years. He loved my dad. He was the one that brought my ol’ man to Blue Note. That’s what got it all started. Lou is from the Charlie Parker school—a real bebopper. We’ve done some concerts together.

JGT: And then Reuben Wilson was another musician who is directly connected with your dad. Grant played on Reuben’s Love Bug album in 1969 for Blue Note, right?

GGJ: Yes indeed. I actually played on Reuben Wilson’s Movin’ On album [2006 Savant Records].

JGT: And was Reuben also in one of your bands?

GGJ: Yeah, he was. The band I was in was called Masters of The Groove—we got a lot of publicity. We played at Lincoln Center for two nights. On the first night, Bernard Purdie played drums; the second night had [legendary James Brown drummer] Clyde Stubblefield…and Lou Donaldson sat in and was playing horn!

JGT: What’s the difference between the two groups—the Godfathers of Groove vs. the Masters of Groove?

GGJ: Well, “The Godfathers of Groove” started out as the “Masters of Groove” and the original members were Reuben Wilson, Melvin Sparks, and Idris Muhammad. But that unit never recorded. Reuben played on my Jungle Strut album [Venus Records, 1998 release]. So I was recruited by the record company, and so was Purdie. Our first recording was The Masters of Groove Meets Dr. No [Jazzateria, 2001 release], the music from the James Bond film. And I must tell you: I thought the record was terrible. I mean, one of songs was “Three Blind Mice!” I just looked at it as a payday. But the record got critical acclaim! And that taught me something, which is this: you never know! Haha! And then we did The Godfathers of Groove album in 2007 with Reuben and Purdie.

JGT: Most jazz guitarists have a sort of “rite of passage” ritual of spending time with organists—you clearly did that when you followed in your dad’s footsteps with Reuben. Were there other legendary organists that you met or played with?

GGJ: Oh yeah, definitely…I played with Jimmy McGriff—near the end, before he passed away. I played with Dr. Lonnie Liston Smith—I’ve known him for years. But I never got a chance to play with Jack McDuff. I did play with [Wes Montgomery organist] Melvin Rhyne though—I went to Europe with him around early ’90s. But my first real gig was with Richard “Groove” Holmes. Truthfully, though, Groove just tolerated me on those gigs—[laughs]—I was really young—I didn’t really know what I was doing.

JGT: Well, everybody’s got to start from somewhere…

GGJ: Yeah, that true…I was cheatin’, playing a lot of triads [hearty laughter ensues]. But he was such a nice guy about it.

JGT: Are people surprised by how different/similar your approach is compared to your dad?

GGJ: I don’t think people are surprised that I sound like my dad, because he was a huge influence on me…but you also have to find your own voice. Everybody is influenced by someone, but the ones that are successful learn from their idols and then goes on and creates his or her own voice. I think a lot of players become clones—but the original is always the best. Because otherwise, people will always end up saying, “Oh, they sound good, but they sound just like…” So, yes—you should definitely try to learn from the greats, but you have to be able to play and be recognized for who you are! Besides, there was already a Grant Green, a Wes Montgomery. There is still already a Kenny Burrell and George Benson.

JGT: To what extent were you involved in that book written by your [then] sister-in-law, Sharony?

GGJ: Just a small contribution—mainly the stuff that I knew and remembered that my other siblings wouldn’t have known because they weren’t there at the times and places I was with my dad—like the gigs he took me on, for example. They weren’t old enough and didn’t have the kind of relationship I did with him, because I was the one who was in Detroit and I was the one who became the musician among all of them.

JGT: Any comments/thoughts about her three-part documentary series on Grant Green she posted on YouTube? I thought it was highly informative, and I kinda wondered if most jazz fans even knew it was out there to see.

GGJ: I think it was rushed because she didn’t have a real budget…and I also think my Mom could have shared a lot of information for the book and the film—she [Mom] should have definitely been interviewed. I think it would have added a lot to the quality and value of it! But like I said before, if she [Sharony] had given me more space, I could have contributed a lot more to the book.

JGT: Like what?

GGJ: Well, a few things…such as: I knew his string gauge. I use the same string gauge—I learned it straight from him. I knew his picks. I knew how he got his tone—a lot of people think it was just his amp, [but] it was also the setting on his guitar—mostly it was that…remember, I used to be his roadie. If you listen to the early albums when he had the Gibson 330, his tone was totally different on Grantstand, than what was on Idle Moments…he also had a specific thing he did using a certain volume level…I know what it was. I was there.

JGT: Wow…

GGJ: And other stuff too—like the fact that I was actually there during the recording of the album Green Is Beautiful at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio.

JGT: Really?!

GGJ: Yep! It was recorded in 1970—and I was at that session. It was the first time that I had been to a real recording session. They had all this food, and beer and sodas and stuff…I was fascinated with the spread that they had! I was about 14 years old—he flew me in from St. Louis. I watched them record, and it was cool. And I was munchin’ out—eating sandwiches, cakes and candy, I was having a ball!! [hearty laughter]

JGT: Tell me the story about you and Grant at a club one night when you helped him remember a tune that he forgot how to play…

GGJ: Yeah, we were in Detroit at the Club Mozambique—his favorite regular gig spot in town. I had written this song…I didn’t yet have a name for it at the time, so I just called it “My Father’s Song,” and he got on stage and was trying to play it, but he forgot the melody. I was in the audience and he waved to me to come up to the edge of the stage. He leaned over the edge and bent down to my ear and I hummed the melody to him in his ear, ‘bah-du-dah, doo-dat dah…[sings the melody]…it was really funny—I got a real kick outta that.

JGT: It seems to me that the move to Detroit in 1970 gave Grant Green a “second life,” career-wise. He had a resurgence of albums, shifted into a successful funk-music phase, and gained an entirely new audience as a result. Was that his plan all along?

GGJ: Well, listen—lemme tell ya somethin’. New York is great—but it’s like a music school. Everybody is there, trying to work, hustle. After a while, it can be exhausting. You wanna get away from that. And he had gotten to a point when he didn’t have to be in New York anymore—he’d already accomplished what he went there to do. I think he really needed to escape to get his family back together, and to have a better life. So, he bought a house, and we ended up there together as a family.

JGT: How different was it living in Detroit as opposed to St. Louis?

GGJ: Oh, a huge difference. A few examples: The Four Tops lived a few blocks away. I lived literally next door to Stevie Wonder—I was good friends with Steve! Here’s another story—I was going to St. Louis one day to visit my grandfather, and my favorite Temptations member—Eddie Kendricks—was sitting right there in the airport. I introduced myself to him, and he was so nice to me—he even bought me a hotdog! Another story: the great Motown bass player, James Jamerson, was one of my dad’s best friends—he came over all the time, used to drive a brand-new Cadillac Fleetwood [tells me a hilarious story about Jamerson letting him drive the car and traumatizing him.]

JGT: Those Motown players could really play jazz too! To what extent have you embraced—or rejected your dad’s general philosophy of, “It’s all [just] music.”

GGJ: It is all music—some good, some bad. I have never been what some people call a “jazz snob.” I would actually argue with some jazz players about the notion of “If it’s not jazz, it’s not music.” My argument has always been, the pop music from the ’30’s, ’40’s, and ’50’s are now jazz standards. There’s just good and bad music!

JGT: I thought one of the greatest descriptions of Grant was made by the St. Louis saxophonist Chuck Tillman who said in the [Sharony Green] book [on p.60] that “Grant didn’t mind being funky. He could play ‘stank’ with the best!” I just love that—stank!!! I know exactly what Chuck means.

GGJ: Yes indeed—musically he was a chameleon—jazz, blues, gospel, soul, funk…whatever you needed. And not everybody can truly play stank!

JGT: Also in the book, [legendary John Coltrane drummer] Elvin Jones says meeting and playing with Grant was “love at first sight.” I thought that was a fantastic thing to hear him say—coming from someone as esteemed as Elvin, that’s high praise, indeed.

GGJ: Yeah, it’s always nice when there’s someone that’s a joy to work with personally and musically who brings out your best!

JGT: How much of an obligation do you feel to uphold your dad’s legacy?

GGJ: Unfortunately, some musicians become more popular when they are gone, so yes—it’s important to keep the legacy going.

JGT: In what ways have you approached making your own mark as an artist to create an identity beyond your father’s obvious musical reputation?

GGJ: Like I said earlier, you have to get your own voice as a player and writer.

JGT: Noted jazz critic Nat Hentoff said he preferred Grant over Wes because his playing is more “conversational.” He also said, “You could recognize him instantly by his tone, phrasing, melodic lines, [and] attack.”

GGJ: Well, that again goes back to having an original voice and phrasing! And especially when you really listen to him—he did a lot of sweeps [right-hand guitar picking technique], it was very horn-like [sings a bebop line]. He played like that because he listened to a lot of single-note instruments, like saxophone.

JGT: Hentoff also mentioned that Grant had a gospel church influence which ultimately was an earmark for Grant’s identity…

GGJ: Yeah, well, there’s a lot of sweet funkiness in that gospel music, too! Dad definitely had that goin’ on! Even church music today has got some of the most funky stuff—it’s always been that way. And one of my favorite records of my dad was Feelin’ The Spirit. I actually covered one of the tunes on that album—his version of “Deep River” on my Introducing G.G. album.

JGT: Tell the readers a bit about that 1996 album, A Tribute to Grant Green [Evidence Records] that you led—it involved some pretty serious heavy-hitters, including Russell Malone, Mark Whitfield, Peter Bernstein, Ed Cherry, and Dave Stryker!

GGJ: Yes! That was a tribute record where we all got together and recorded my dad’s songs—oh wow, I totally forgot about that record, I don’t remember everybody that’s on it!

JGT: Russell, Mark, Peter, Ed, and Dave—a murderer’s row!

GGJ: Wait a minute—was Joshua Breakstone on it too?

JGT: No, but I recently spoke to him about you, coincidentally! By the way, he did an absolutely fantastic tribute to your dad—Remembering Grant Green, recorded in Japan in 1993 [released in 1996 in the U.S. on Evidence Records]. Joshua just told me he met you in Corsica—

GGJ: Oh yeah, Joshua and I met in Corsica, for a Jazz Festival in France. It’s really beautiful there—and great food too!

JGT: Let’s talk a bit about how the Jungle Strut (1997, Venus Records) album came about?

GGJ: That was funny—Todd Barkan asked me to do this session so I agreed. When I got to the studio, I asked where the Todd Barkan session was and they said, “There is no Todd Barkan session here.” So I’m like, “What the hell?—I got here so early in the morning…” So finally I asked, “What sessions do you have?” and the receptionist said, “We have a Grant Green, Jr. session.” I did not know it was my session! That album got great reviews—it was a very old school project—I did not pick any of the songs. Todd did some of those songs, tunes I would have never picked! That album—if you can find it—cost forty dollars or more—it’s crazy!

JGT: How did you come to know Barkan?

GGJ: Todd Barkan owned the Keystone Korner in San Francisco; he was also music director for Lincoln Center…I’m not sure how we met. [Side note: Barkan is indeed a multi-talented music entrepreneur who wears many hats: club owner, manager, producer, record label executive, concert series director, etc.]

JGT: Oddly enough, Todd’s name is nowhere on the record—he’s not even listed as the producer…

GGJ: Well, he was! Maybe he got paid cash under the table! Have you seen the price for that CD?

JGT: Yeah I’m tryin’ to buy it, but it’s ridiculous—like seventy bucks on the market, and only two copies available, and from sellers in Japan—I assume mainly because Barkan was the head of Venus, which was based in Japan…

GGJ: That’s crazy—I have not seen a dime!

[JGT Note: I did buy the CD—I couldn’t resist. I had to know what this album sounded like, and it is not available on Spotify, Tidal, or iTunes, so…]

JGT: Oh, and I also see here that there’s the price tag of $100 for a vinyl copy!

GGJ: Really! I didn’t think it was a good record either…but the critics liked it—just goes to show what they know!

JGT: Wow. Ok, so while we’re at it, why don’t we discuss the SoulScience album released on the Ropeadope label. It was recorded in Atlanta in 2015 and released in 2016. So, what’s the story on that project?

GGJ: Well unfortunately, I had not released anything in a while. So, I had to get something out and I wanted to something that was not all jazz-oriented or just guitar-oriented, I have always loved all types of music and I guess that’s my Motown roots showing. But it [the album] could have been done better. I thought I had to get something out because it had been a while.

JGT: Who arranged the music for all those horns? There’s a lot of people on that album!

GGJ: Jonathan Lloyd, the trombone player on the album.

JGT: What was your relationship with company owners of Ropeadope—Louis Marks and Fabian Brown? How did your deal with them come about? Was it the only album you did with them?

GGJ: I actually knew those guys when they were selling these Blue Note T-shirts and my bass player Khari Simmons knew them too. And yes, it was the only recording I did for them.

JGT: I kinda wish they had released a hard copy version of it…

GGJ: They really didn’t promote it!

JGT: Yeah I was wondering about that…

GGJ: And I think they had it placed in the R&B category of their catalog.

JGT: Did I read on Ropeadope’s promo page that you used to play with Col. Bruce Hampton???

GGJ: Yes, I did. I loved Bruce—what a great guy!

JGT: How did that happen?? How did you get recruited in that troupe?

GGJ: When I played in Atlanta, he came to the show when I was with The Godfathers of Groove—that’s when I first met him. When I moved from New York to Atlanta he was one of the first people to call me. I had been here maybe a week, when I get this call; he asked me what I was doing over the weekend, and I said, “Nothing!” He said, “You are working with me!” And we were tight ever since!

JGT: Wow! Were you there at that legendary tribute concert they gave for him in Atlanta?

GGJ: I was there.

JGT: What’s the most recent thing you have released?

GGJ: I had a house song out this year—called Running.

JGT: What’s this—a new house tune you’re speaking of? Tell me about it—I’m not aware! [New York City DJ and house music mixer] Lenny Fontana and I did it…years ago when I lived in NYC.

JGT: Ok, tell me how it happened.

GGJ: I don’t even remember—it was so long ago…I think it was the early 2000s.

I looked it up—they got a lotta different mixes of it—club, guitar, a cappella…

GGJ: Yep—they did a lot of that back in the day.

JGT: Let’s discuss your current solo album projects—what do you have on the horizon?

GGJ: Well, I’m working on a couple of things—one is a Burt Bacharach songbook.

JGT: Oh, I’d love to hear about this project!

GGJ: He wrote so many great classics…I mean, come on—“Alfie?” “Wives and Lovers?” These are great tunes, man.

JGT: Is the album already finished?

GGJ: No—listen, man—when we started working on that album, just as soon as we jumped in it—this damn COVID shit hit across the entire country.

JGT: What do you plan on naming the project when it’s done?

GGJ: I think it may just be, Thank You Mr. Bacharach.

JGT: You have a label already lined up for it?

GGJ: I still have strong connections to Blue Note Records through my dad’s legacy—I think I might send it to them. We’ll see what happens. And you can never write enough original music, so there’s going to be an original album forthcoming too.

JGT: I’m sure our readers will really be looking forward to hearing that—thanks for sharing your time and energy with us.

GGJ: You bet—thanks for inviting me, brother—I really enjoyed doing this interview. I don’t do a lot of ’em, but this was great fun.

JGT would like to thank Grant Green, Jr. and Wayne Goins for the interview!

ALL PHOTO PERMISSION GIVEN BY GRANT GREEN, JR.

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons2 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Analyzing “Without A Song”

-

Jazz Guitar Lessons4 weeks ago

New JGT Guitar Lesson: Considering “Falling Grace”

-

Artist Features1 week ago

New Kurt Rosenwinkel JGT Video Podcast – July 2024

-

Artist Features3 weeks ago

JGT Talks To Seattle’s Michael Eskenazi